“Reality is greater than the sum of its parts, also a damn sight holier.”

Sometimes a Great Notion by Ken Kesey

A few weeks ago, I went to a workshop about awe and wonder. As my mom would say, that’s so California.

The workshop was led by Dacher Keltner, Ph.D., the founding director of the Greater Good Science Center and a professor of psychology at UC Berkeley, known in the social psychology community as “THE awe guy.”

According to his research, there are eight “wonders of life” that are most likely to lead to awe:

Moral Beauty, the observation of deep human kindness

Nature, fairly self-explanatory

Life & Death, being close to either side of the life cycle

Collective Effervescence, the feeling you get when everyone’s doing the same thing at the same time

Visual Design, think art, aesthetics, architecture

Big Ideas, from scientific breakthroughs to a-ha moments

Mystical Experiences, with spirits (or psychedelics)

Music & Poetry, when lyrics take your breath away

It felt ironic to learn about awe from a PowerPoint, though we did take a break to watch the sunset.

Sometimes it feels like social science spends a lot of time codifying something that people already intuitively know or experience. But other times, learning about a universally human phenomenon helps you learn about yourself.

I studied psychology in college. I generally buy the idea that if you are made aware of the benefits of something like awe, you can cultivate it with greater intention.

But when it comes to awe, my greatest teacher isn’t Dacher Keltner, it’s my mom.

My mom writes poems. Sometimes, they’re about me. For Becky.

One poem described a moment from when I was a teenager. My mom and I were sitting in the car at the library. We saw a fox—fixed, frozen, eyes up, not sure if it was coming or going.

The poem was about that in-between time, between high school and college, not sure if you’re coming or going. No longer a kid, not quite an adult. Fixed, frozen, eyes up.

My mom falls fast into awe. She sees a fox in a parking lot and makes us both stop to look, to wonder where it’s going, where it’s coming from, and how it might be feeling in the moment.

As kids we used to make fun of her, my siblings and I, for always pointing things out. She’d narrate the world around her as if it were a nature documentary, even though we lived in the suburbs of New Jersey.

She says she gets the narrating from her mom, who passed before I was born.

It turns out, many of my mom’s poems are about awe. Like Mary Oliver, she pays attention, is astonished, and tells about it. Tells us kids anyway.

There’s the one about the fox, the one about the shard of pottery, the one about the bud within the bud.

I once heard that the egg you were born from was already present in your grandmother’s body when she was pregnant with your mom.

The bud within the bud within the bud.

It turns out, I narrate things, too.

I can’t make it 5 minutes without stopping to point something out.

Did you see that flower that looks like it’s from a Dr. Seuss book? Did you see how the light reflected off that window like a disco ball? Did you see the way those leaves fell and landed right next to each other, perfectly parallel?

We are same, same, she says. Same, same, same.

At our wedding, my mom read a Mary Oliver poem. “Joy is not meant to be a crumb,” she said.

I looked out at all of our guests, sitting in the rain, umbrellas up, paying attention.

At work, I learned how to use a technique called Visual Thinking Strategies, or VTS, borrowed from art education.

VTS involves posing three simple questions: What’s going on in this picture? What do you see that makes you say that? What more can you find?

Basically, if you stare at something long enough with curious eyes, things will start to emerge—new connections, new details, new observations.

It’s a strategy to cultivate deeper understanding of an image, and for me, a way to drop into awe.

When we first moved to Gualala, it was common for friends from the city to ask, “Won’t you get bored? What will you do on weeknights?”

First of all, what do you do on weeknights?

Kidding aside, it’s a valid question. There are less places to go and presumably less things to do.

What’s going on in this picture?

There are no streetlights, so I’m not very motivated to be on the road at night. We can’t walk to town from our house, the double edged sword of privacy. We’re still making the kinds of friends you have over just to hang out on a weeknight.

On the surface, it is quieter.

What do you see that makes you say that?

There are less inputs, less interactions. More sky, more space.

Our few neighbors are kind. We mostly keep to ourselves, though we wave when we pass by.

But if you pause for a moment, you’ll hear frogs. You’ll see fairy rings. You’ll find mushrooms.

You’ll notice the teenagers working at the supermarket flirting with each other.

You’ll overhear conversations about trying to find work and whether it’s worth it to get certified as a contractor or keep working under the table.

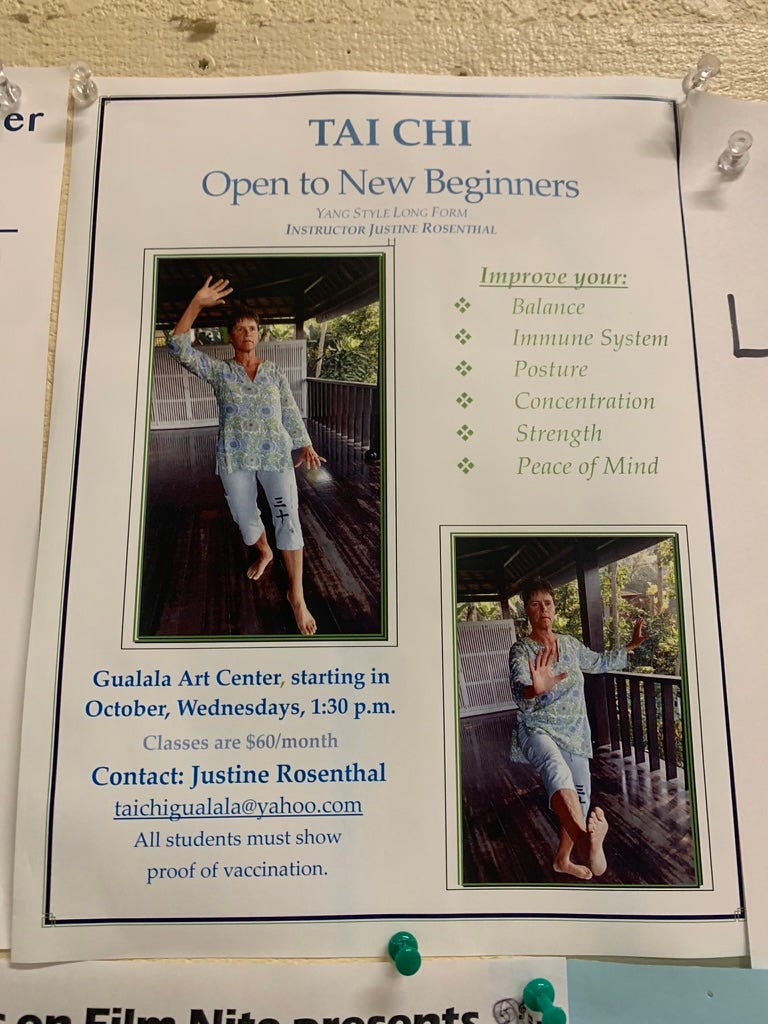

You’ll read the flyers at the post office about tai chi classes and rockfish trips and Sonoma County Funk, with long links that you have to type into your phone browser by hand.

You’ll become aware of the texture of the place, the complexity of the community.

What more can you find?

There’s less noise, but not less sound. The closer you look at what seems like sameness, the more you find novelty. To me, that feels a whole lot like awe.

In 2020, a few months into the pandemic, I noticed myself falling out of awe. I wasn’t inspired, even by objectively inspiring things. I felt trapped in my house, and in my computer.

I was living in the Outer Sunset in San Francisco. With the whole country on lockdown, I started going on walks around my neighborhood.

I walked slowly, with no destination. I let the dog sniff whatever she wanted.

I’d walk by the same houses I’d been walking by for months. I stared at the same street corners and the same sidewalks.

I started taking photos of whatever was around.

The more I stopped to look, the more I found myself noticing things I hadn't seen before—a bright flower against an even brighter house, figurines nestled in a windowsill, a pair of chairs set out for whoever needed a break.

Little signs of life. Little pieces of art.

Instead of feeling trapped, I felt more present, more curious, and more connected to where I lived.

Who lives in the house with a dove painted on the awning? Who built a wishing well next to their front door? Who carefully placed bowling balls on their yard?

I don’t know exactly which of the eight wonders these experiences would count as—the Visual Design of lawn tchotchkes? The Moral Beauty of Little Free Libraries? The Collective Effervescence of living and working and eating and sleeping in 700 square feet next to someone else’s 700 square foot life?

Regardless, I started to feel like myself again.

It turns out, awe is one of my vital signs.

It’s up there, keeping me alive, right next to the number of times my heart beats per minute.

My baseline is to find awe wherever I am—in small things, big things, incredibly basic things.

Air travel. How matches work. The fact that everyone in the whole world is looking at the same moon.

If I feel myself losing my sense of awe, I know something is off. And I know how to revive myself, wherever I am.

Because, to me, finding awe isn’t about where you are, but about how you are.

It’s taking a moment with your daughter in the car before she leaves for college.

It’s reading a poem at her wedding, in the rain, instead of rushing everyone inside.

It’s walking slowly with no destination, and finding art all around.

It’s pausing, paying attention, and making space for awe to drop in on you.

What more can you find?

“It turns out, awe is one of my vital signs.”

Powerful and insightful words. I loved this entry so much. Your words are poetic, just like your mothers.

Your mooooooom 💓💓💓