“A tree can be only as strong as the forest that surrounds it.”

The Hidden Life of Trees by Peter Wohlleben

The day after I hit publish on my first post, waxing poetic about living in the woods and foraging for mushrooms, a series of massive wind and rain storms swept the northern California coast.

It’s January 4th, a typical Wednesday morning. We wake up, brush our teeth, make coffee. We know it’s going to be a rainy day, so we take the dog for a quick walk before starting work.

A few hours after the rain starts, we see reports of trees down nearby on the local Facebook page. Trees down means power lines down means power out.

Not long after, our power goes out, too.

We consider ourselves to be pretty hardy. We don’t mind rain. We’re used to East Coast snow storms. We love camping.

So, we set up a propane stove on a covered patio, grab some blankets, and start a puzzle while it’s still light out. We use cell service to shoot Slack messages to our colleagues to let them know we are officially OOO.

We hear something fall on the roof. And then another something. At least one of those somethings is a branch, thick as your arm, big enough to see hanging over the edge of the gutters.

Suddenly, the surrounding trees go from grand, perspective-offering totems to big chunks of timber that could fall on our house.

We wonder where the safest part of the house might be, if there is a safest part of the house.

We hear a louder crash. We freeze for a minute, trying to assess where the sound came from and how close it was. We run from window to window until we see it.

A 50+ foot fir tree is down, completely uprooted. Luckily, it fell parallel to the house, though it did take down a row of string lights.

20 minutes later, we find ourselves sitting in the supermarket parking lot because it’s the only place we can think of that doesn’t have tall trees.

We try to wait out the storm, a bit damp, clutching hands, with the dog panting in the backseat.

New Slang comes on the radio, the song Natalie Portman tells Zach Braff is “gonna change your life,” in the movie Garden State.

I have a small smile on my face, as I briefly romanticize my life, mid-crisis.

At this point, we’re not sure where to go. We regrettably put off getting a generator. The few local hotels don’t have power either. But it’s not really about the power. It’s about the trees.

We head back home to gather some gear. It’s late afternoon by now. Winds are expected to hit over 60 miles per hour by 5pm, right around sunset.

From inside the house, we hear the wind picking up, whistling and whooshing through the trees. We see treetops swaying across the yard, looking more like reeds than redwoods.

If we sleep here, we submit to a night of wondering if—or when—a tree will fall on us.

We immediately call Surf Motel, a small inn in town, who graciously waives their pet fee. They tell us the room doesn’t have power, but it does come with a candle.

Adrenaline pumping, we grab whatever we can fit in our backpacks. Underwear. Lanterns. Toothbrushes. Dog food.

It starts to get dark and we take off down the same road we came up ten minutes earlier. A new tree is down, blocking us from passing.

We back the car up slowly and turn around, hoping the only other way to town is clear. We head up past our house and take a left onto a back road.

It’s one of those no music, don’t-say-a-word drives, both of us silent as we roll over tree limbs and pass by dangling power lines, one barely a foot above the car.

We make it to the hotel and light the candle. I look in the mirror and realize my sweatshirt is on backwards. We throw a blanket on the bed for the dog and fall into a restless sleep.

Since we’ve moved to Gualala, I’ve learned one thing for certain—nature is powerful.

When an old-growth redwood is cut or downed, new trees can sprout from its roots, forming a circle around the elder tree, also known as a fairy ring.

The new generation is fed and sustained by the same root system of the previous generation, giving them a stronger starting point than trees grown solely from seeds.

Those root systems are surprisingly shallow, only about five or six feet deep, but can extend over 100 feet away, intertwining with the roots of other trees for greater stability.

The trees are what drew us here, what compelled us to stay. Their bigness, our smallness.

Turns out the line between awe and fear is 60 mile per hour winds.

At some point you have to ask, is it worth it? Is living here, at nature’s great whims, worth it?

We’re going on 72 hours without power. The two gas stations in town ran out of gas and the refill trucks couldn’t pass on the roads. The local fire crew is fully staffed by volunteers who have been clearing trees nearly as fast as they come down.

With rationing comes reverence.

Here, I have a renewed gratitude for everything I used to take for granted, like clean running water and consistent heat (even if I did grow up in a “just put a sweatshirt on” household).

There’s a healthy surrender, an acceptance that nature really is in charge.

I’m also more acutely aware of nature’s abundance.

Like the feeling of looking out at the ocean and not being able to see land on the other side.

Or looking down and discovering a cluster of mushrooms that sprung up overnight.

Or looking up and registering your relative insignificance to trees over a hundred feet tall.

Part of the draw of a place like this is how regularly you’re confronted with your own insignificance, and even your own mortality. You are small and life is short.

The tiff with your roommate, the parking ticket, the passive aggressive tone a client used—none of it feels that important when you walk outside and put your hand on the bark of a tree that has already been alive for a century, will almost certainly outlive you, and if it falls in a certain way, could even take your life.

But, is it worth it? Are old, big trees worth it?

When it comes to deciding where to live, we millennials have inherited the morbid game of “choose your own natural disaster.”

I’ve spent enough hours trying to calculate the risk of various place-based natural disasters to realize that climate change is real everywhere.

Are 5 month winters worth it? Or 115 degree summers? Or avalanche warnings? Or flood zones? Or hurricane seasons?

How do you balance these environmental realities with the other things you might value—fresh produce, good public schools, racial diversity, political alignment, natural wonders, great architecture, nearby family, stable jobs?

No place is perfect.

To have a choice of where to live is a great privilege in itself.

In taking that privilege seriously, I reflect on my values, interrogate tradeoffs, and make carefully balanced calculations.

Yet after living somewhere for a whole year—even starting a newsletter about how much I like it—a huge storm comes and throws another variable into those carefully balanced calculations.

Because in practice, places don’t exist just for us.

Places aren’t fixed entities to plug into. They aren’t meant to cater perfectly to your every need. They’re living, breathing, communities—root systems that existed before you and will continue to exist, with or without you.

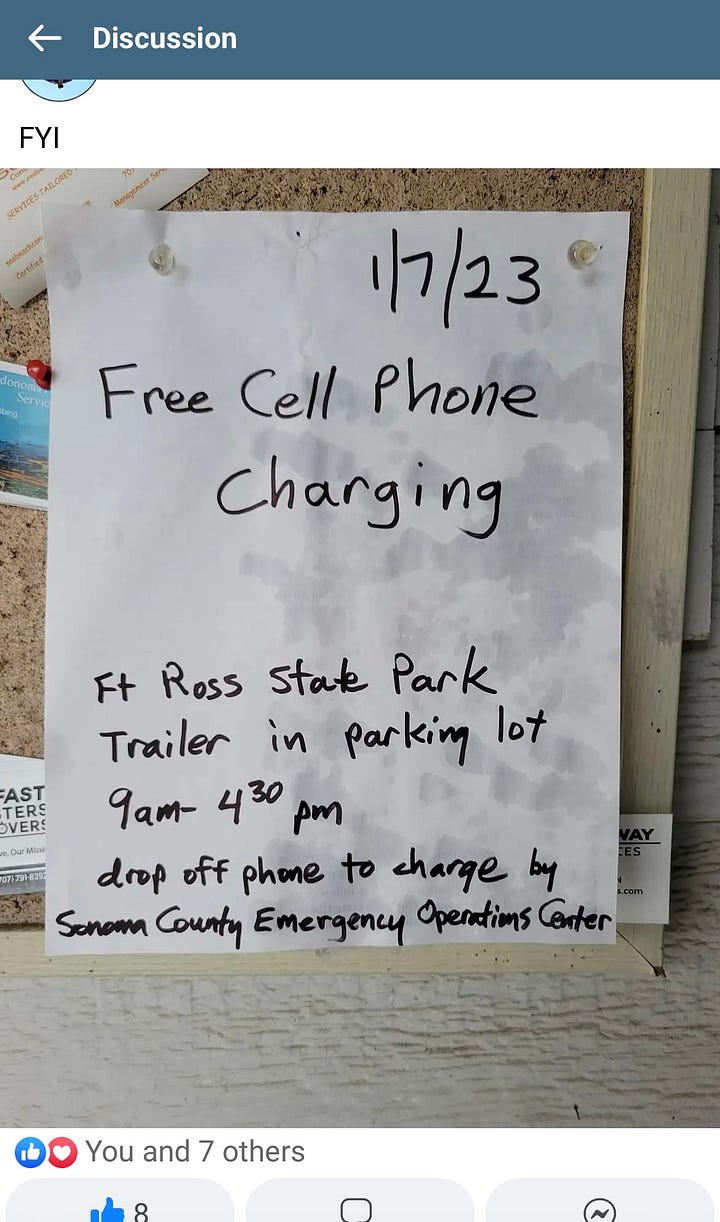

During the storm, we checked the local Facebook group nonstop. People were sharing ice packs, firewood, and access to generators, coordinating available housing for PG&E crews coming in from other states.

There were real time updates on trees down and flooded roads and school closures and lost pets and power restoration.

There was even a post about extra pizza dough, and of course, the occasional meme.

We got flurries of texts from neighbors—“Let us know if you need anything!” “You can come cook at our place!” “We have a chainsaw if you get stuck!”

Seeing the community come together made me think, maybe it’s less about where you choose to be, and more about what you choose to pay attention to.

One person’s crisis is another person’s close-knit community.

Sometimes, I worry that moving around means never putting down roots anywhere.

There’s already a root system here. There has been for generations.

Maybe, someday, I can join it.

But the truth is, I already have a root system, too. It may be shallow, but it’s as wide as a country. And it gets stronger as it expands.

Maybe, someday, I can weave them together.

An enormous thank you to the volunteer firefighters of the South Coast Fire Protection District and PG&E crews in Gualala for getting our roads clean and our power back on.

Becky thank you for bringing us along a vivid sodden journey. I was with you in that quiet car. And thank you for a new phrase that will sit with me for a while: "With rationing comes reverence." Profound and applicable to the more areas of life the more you consider it. And I'm so grateful you have power restored!

Thank you for transporting me to your place and moment and emotion. You've chosen a wonderful community to be a part of. The story you reveal reminds me of the phrase Ichigo Ichie which is sometimes translated as "in this moment, opportunity". You seem to have savored the moment in spite of the uncertainty is presented. I'm glad everything is well with you.